Revolt of the Homo Ludens

Hi.

Welcome to Free Association, a newsletter about collective creativity. My name is Juha and I am an artist, organiser and educator based in Amsterdam.

For years my main artistic expression was that of creating clubs nights, and performing during them. But as a result of the covid lockdowns, I have started to make moving image work about the revolutionary potential of collective creativity.

This did not come out of nowhere, as I have been involved in commissioning, producing and teaching moving image art and audiovisual expression for some time now, with e.g. Anonymous, Progress Bar and Resolution.

So here we are, again.

This took a bit longer than anticipated. Life got in the way.

The last time I said I would look at the influence of Johan Huizinga’s concept of the Homo Ludens (man at play) on Constant’s New Babylon project. And then I got stuck reading everything about Homo Ludens again, from Homo Ludens and Man, Play and Games, to Provo and Het Witte Gevaar.

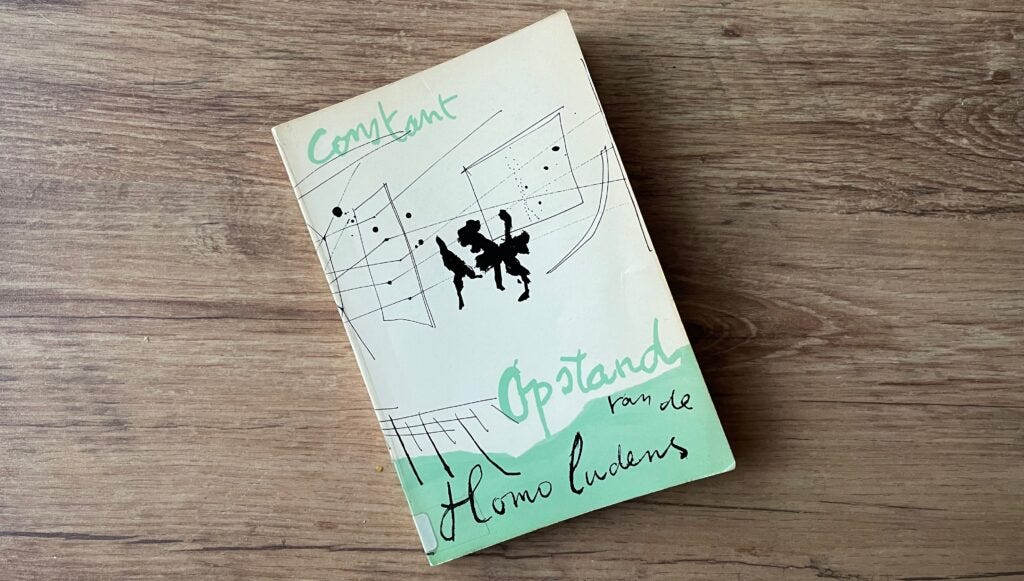

But the best source for Constant’s interest in Homo Ludens is his out-of-print book Opstand van de Homo Ludens (Revolt of the Homo Ludens). The book was published in 1969, and contains articles written by Constant between 1964 and 1967.

The book is a beautifully designed collection of brilliant articles of an artist in his prime. I didn’t know the book until I visited his house and private library a few years ago on the invitation of Fondation Constant. They were selling the house after his death, and had invited some artists to come by one more time for inspiration. I did, and I spent hours photographing his books, and among them I found this one.

As the book has not been published in English, I have decided to translate it myself. In this newsletter, I am sharing the preface, and I intend to share the remainder of the articles in the coming months. I will try to translate more relevant texts to the RoXY research, as I found out quite a few anarchists and communists who wrote in Dutch have not been translated into English yet.

Revolt of the Homo Ludens

Preface

Die, ye old forms and thoughts.

Slave-born, awaken, awaken.

The world drifts on new forces.

Desire has touched us.

The International

The resistance, especially of young people, to the so-called "consumer society”—by which one means the society of wasting gained production capacity, of aggressively marketing products no one needs, of plundering our living space, of confiscating the air we breathe, of manipulating scientific and artistic research, of falsifying ideas—resistance to this society in which we live is strikingly and increasingly accompanied by the emergence of playful modes of behaviour. Besides criticism and reasoning and consequent demonstrative actions, manners, language, appearance, in short the overall way of life are used as weapons in the social struggle. In the revolution, fantasy finally begins to play a clear role. Important here is the fact that this time no other equivalent pattern is set against the usual pattern of behaviour—that would soon be socially assimilated as experience shows—, that the face of the revolution is thus not a variant of a familiar face, but that a real game is being played with norms, customs and associations, a game that can range from wordplay to the inversion—‘détournement’—of symbols, of cultural forms, of ways of thinking, detached from their traditional context. By no longer adhering to the rules of the game—rules obviously dictated by the 'establishment’—the insurgents become elusive; one never knows in advance how to recognise them or how to design suitable countermeasures against their actions.

When I wrote in 1949, in the fourth issue of Cobra: 'Freedom can exist only in creativity or struggle, which au fond have the same goal: the realisation of our lives', I would not have dared to expect that already 20 years later these social struggles and creative invention would be so intertwined. The cause must be sought in automation. Automation is creating a growing army of, mainly youthful, unemployed people, people without possessions, trained for a trade that will be obsolete even before this training is finished, 'workers' who will never work, professionally unemployed. The energy of this youthful proletariat, no longer consumed in the labour process, must discharge into another, non-utilitarian activity. The so-called 'tertiary' is an escape solution. We need only take a historical look back at the activities of the non-working upper class to know that this new activity will be of a ludic nature. The economic conditions for a ludic mass activity, for a culture of the masses, are in place. The contractions of this culture have begun.

“Today's students, unlike those of the past, are dispossessed, disenfranchised and exploited, and their fate is not much different from that of the industrial proletariat.” — Constant

The texts brought together in this volume were written in the years between 1964 and 1967, i.e. in the years preceding the students' actions. It therefore makes sense to dwell on this new aspect of the social struggle. Although attempts were made, also on the left, to isolate the student actions and maintain a separation between the student youth and the workers, it must be noted that the main cause of the radicalisation of the students was precisely the fact that automation led to a proletarisation of the intelligentsia. Today's students, unlike those of the past, are dispossessed, disenfranchised and exploited, and their fate is not much different from that of the industrial proletariat.

Disenfranchised, they are, because the efforts of their studies offer no guarantee for the future; exploited, because they cannot exercise any control over the manner in which the result of their labour—scientific research—is used. The computerised business needs less workers in overalls, but all the more scientifically-trained personnel. University education is being adapted to this need. Instead of aiming at the development of thinking, universities aim at cultivating professionals who, apart from a specialised field, have no development. The right to research is smothered in dependence on technical 'equipment' controlled by the industrial concentration of power. Control of production by the worker has become a futile endeavour when not coupled with it is the endeavour to control university education by the students. At present, the results of scientific research are being expropriated and the intellectuals rendered powerless. That is the background of the students' revolt and that connects this struggle with that of the workers in the factories and with the street actions of the disaffected youth who are no longer involved in the production process, nozems or whatever one wants to call them.

“The masses have smelt the freedom that has come within their reach, desire has touched them. It will not rest until this desire is satisfied.” — Constant

The alternative to this manipulated society of the tertiary is the free society of creative people. Against the concentrated power of monopolised capital stands the growing mass of dispossessed and disenfranchised, intellectuals and workers, who demand the right to benefit from automation, from the resulting increases in production, who want to eat the fruit of the tree they themselves planted, who want to enjoy the freedom that has potentially become possible.

The masses have smelt the freedom that has come within their reach, desire has touched them. It will not rest until this desire is satisfied. The massification of culture began with the revolt of Homo Ludens.

The Society of the Homo Ludens

I think Provo adored Constant’s writing as much as his art. They wanted to actually realise his New Babylon models, and tried to do so in Amsterdam. But they also published his words, and wrote about his ideas of a society of the Homo Ludens in their magazines. In the video below it is Jacqueline de Jong who talks about Constant, Provo and the Homo Ludens.

I also think that even though some people know and like Constant’s work today, especially architects and architecture students it seems, I do think few people are familiar with his writing. And one reason is that his writing has been out of print, another is that is has not been widely translated, meaning it has been kept from reaching a mass audience interested in revolutionary art and politics. I hope by translating him I can help change this.

Free Palestine

Thanks for reading until the end. I’m off for a drink now, but I will pick up this translation game soon since I enjoyed it so much.

I will leave you not with a video from RoXY or my research, but with a quote from Toni Cade Bambara and a video from recent protests in Amsterdam in solidarity with Palestine. Because Amsterdam is saying no to genocide.

Free Palestine,

Juha

“The role of the artist is to make the revolution irresistible.” — Toni Cade Bambara